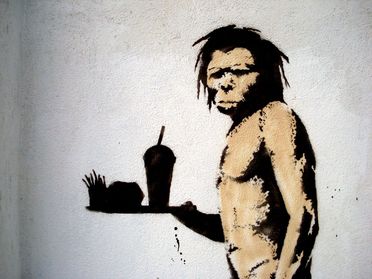

Cave Man's Diet...

Paleolithic Nutrition:

Your Future Is In Your Dietary Past

Jack Callahan, 1997

Just as individual genetics and experiences influence your nutritional requirements, millions of years of evolution have also shaped your need for specific nutrients. Thus a diet of lean meat, fish, fruits and vegetables is now considered to represent a Paleolithic Diet and such a diet is basically that to which humans are genetically adapted.

The implications? Your genes, which control every function of your body, are essentially the same as those of your early ancestors. Feed these genes well, and they do their job - keeping your healthy. Give these genes nutrients that are unfamiliar or in the wrong ratios, and they go awry - aging faster, malfunctioning, and leading to disease.

According to S. Boyd Eaton, M.D., one of the foremost authorities on paleolithic (prehistoric) diets, modern diets are out of sync with our genetic requirements. He makes the point that the less you eat like your ancestors, the more susceptible you'll be to coronary heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and many other "diseases of civilization."1 According to Eaton, 99 percent of our genetic heritage dates from before our biological ancestors evolved into Homo sapiens about 40,000 years ago, and 99.99 percent of our genes were formed before the development of agriculture about 10,000 years ago. "That the vast majority of our genes are ancient in origin means that nearly all of our biochemistry and physiology are fine-tuned to conditions of life that existed before 10,000 years ago," he says. Looked at in another way, 100,000 generations of people were hunter-gatherers, 500 generations have depended on agriculture, and only 10 generations have lived since the start of the industrial age, and only two generations have grown up with highly processed fast foods.

"The problem is that our genes don't know it," Eaton points out. "They are programming us today in much the same way they have been programming humans for at least 40,000 years. Genetically, our bodies now are virtually the same as they were then."

Because the human genome has changed relatively little in the past 40,000 years since the appearance of behaviorally modern humans, our nutritional requirements remain almost identical to those requirements which were originally selected for stone age humans living before the advent of agriculture.

Based on contemporary studies of hunter-gatherer societies, early humans consumed relatively large amounts of cholesterol (480 mg daily), but their blood cholesterol levels were much lower than those of the average American (about 125 mg per deciliter of blood). There are a couple of reasons for this.

One, domestication of animals increases their saturated fat levels and alters the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids. Most Americans consume an 11:1 ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids. But a more ideal ratio, based on evolutionary and anthropological data, would be in the range of 1:1 to 4:1. In other words, our ancestors consumed a higher percentage of omega-3 fatty acids - and we probably should too.

Two, gathering and hunting required considerable physical effort, which means early humans exercised a lot, which would have burned fat and lowered cholesterol levels. "Their nomadic foraging lifestyle required vigorous physical exertion, and skeletal remains indicate that they were typically more muscular than we are today," says Eaton. "Life during the agricultural period was also strenuous, but industrialization has progressively reduced obligatory physical exertion."1

Our evolutionary diet provides important clues to the "baseline" levels and ratios of nutrients needed for health. The evidence suggests we should be eating a lot of plant foods and modest amounts of game meat, but no grains or dairy products. With a clear understanding of this diet, we have an opportunity to adopt to a better, more natural diet. We can also do a better job of individualizing and optimizing our nutritional requirements.

1 Eaton SB, Eaton SB III, Konner MJ, et al., "An evolutionary perspective enhances understanding of human nutritional requirements," Journal of Nutrition, June 1996;126:1732-40.

Your Future Is In Your Dietary Past

Jack Callahan, 1997

Just as individual genetics and experiences influence your nutritional requirements, millions of years of evolution have also shaped your need for specific nutrients. Thus a diet of lean meat, fish, fruits and vegetables is now considered to represent a Paleolithic Diet and such a diet is basically that to which humans are genetically adapted.

The implications? Your genes, which control every function of your body, are essentially the same as those of your early ancestors. Feed these genes well, and they do their job - keeping your healthy. Give these genes nutrients that are unfamiliar or in the wrong ratios, and they go awry - aging faster, malfunctioning, and leading to disease.

According to S. Boyd Eaton, M.D., one of the foremost authorities on paleolithic (prehistoric) diets, modern diets are out of sync with our genetic requirements. He makes the point that the less you eat like your ancestors, the more susceptible you'll be to coronary heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and many other "diseases of civilization."1 According to Eaton, 99 percent of our genetic heritage dates from before our biological ancestors evolved into Homo sapiens about 40,000 years ago, and 99.99 percent of our genes were formed before the development of agriculture about 10,000 years ago. "That the vast majority of our genes are ancient in origin means that nearly all of our biochemistry and physiology are fine-tuned to conditions of life that existed before 10,000 years ago," he says. Looked at in another way, 100,000 generations of people were hunter-gatherers, 500 generations have depended on agriculture, and only 10 generations have lived since the start of the industrial age, and only two generations have grown up with highly processed fast foods.

"The problem is that our genes don't know it," Eaton points out. "They are programming us today in much the same way they have been programming humans for at least 40,000 years. Genetically, our bodies now are virtually the same as they were then."

Because the human genome has changed relatively little in the past 40,000 years since the appearance of behaviorally modern humans, our nutritional requirements remain almost identical to those requirements which were originally selected for stone age humans living before the advent of agriculture.

Based on contemporary studies of hunter-gatherer societies, early humans consumed relatively large amounts of cholesterol (480 mg daily), but their blood cholesterol levels were much lower than those of the average American (about 125 mg per deciliter of blood). There are a couple of reasons for this.

One, domestication of animals increases their saturated fat levels and alters the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids. Most Americans consume an 11:1 ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids. But a more ideal ratio, based on evolutionary and anthropological data, would be in the range of 1:1 to 4:1. In other words, our ancestors consumed a higher percentage of omega-3 fatty acids - and we probably should too.

Two, gathering and hunting required considerable physical effort, which means early humans exercised a lot, which would have burned fat and lowered cholesterol levels. "Their nomadic foraging lifestyle required vigorous physical exertion, and skeletal remains indicate that they were typically more muscular than we are today," says Eaton. "Life during the agricultural period was also strenuous, but industrialization has progressively reduced obligatory physical exertion."1

Our evolutionary diet provides important clues to the "baseline" levels and ratios of nutrients needed for health. The evidence suggests we should be eating a lot of plant foods and modest amounts of game meat, but no grains or dairy products. With a clear understanding of this diet, we have an opportunity to adopt to a better, more natural diet. We can also do a better job of individualizing and optimizing our nutritional requirements.

1 Eaton SB, Eaton SB III, Konner MJ, et al., "An evolutionary perspective enhances understanding of human nutritional requirements," Journal of Nutrition, June 1996;126:1732-40.